NBE is the oldest commercial bank in Egypt It was established on June 25 1898 with a capital of £ 1 million Throughout its long history NBE's functions and roles have continually developed to square with the different economic and political stages in Egypt During the 1950s NBE assumed the central bank's duties After its nationalization in the 1960s it acted as a pure commercial bank besides carrying out the functions of the central bank in the areas where the latter had no branches Moreover, since mid-1960s NBE has been in charge of issuing and managing saving certificates on behalf of the government

Samir Raafat

Cairo Times (unedited version), June 11, 1998

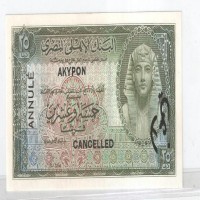

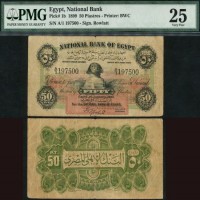

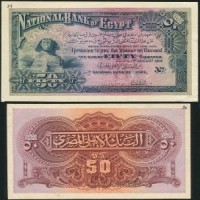

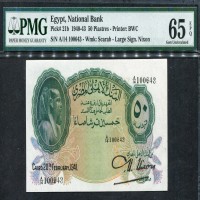

Sixteen days after it was incorporated in London, from his Alexandria Palace of Ras al-Teen Abbas Hilmi II rubber stamped a landmark decree on 25 June 1898, creating the National Bank of Egypt. In so doing, close observers remarked the khedive had initiated Egypt's embryo central bank. Unlike earlier banks, this one would have the exclusive right to regulate and issue notes, a privilege which it exercised the following April until 1960.

Besides their shared sensibility in finance, the bank's three promoters enjoyed a stamina common only to shrewd immigrants with a most definite purpose.

Sir Ernest Cassel, National Bank of Egypt's largest founding shareholder, was a German Jew-turned-gentile who adopted England as his new homeland. His connection to Egypt stemmed from an early apprenticeship at the Anglo-Egyptian Bank in Paris. Trampling on old-fashioned conventions, he became the richest man in England and advisor to King Edward.

Raphael Suares, the son of an immigrant Jew from Leghorn Italy, built for himself a financial empire in Cairo. With his two brothers, Felix and Joseph he founded the Credit Foncier Egyptien and from there created a huge private consortium which dealt in almost everything, from real state development to rail transport and sugar refineries. In time, Suares became the khedive's financial advisor.

Constantine Salvago who, like Suares, put up 25% of the new bank's capital, was an immigrant from the Dodecanese Iland of Chios. A sometime textile merchant in Marseilles, Salvagos arrived in Alexandria just as the American Civil War sent Egyptian cotton prices soaring. No advisor to monarchs Salvago would become Egypt's cotton king.

Those who speak of privatization today may not realize that we've been down this road before thanks to Messrs. Cassel, Suares and Salvago. Coinciding with the creation of the National Bank of Egypt, was the sell-off of Daira Sanieh, the country's largest state-run company.

A former khedivial estate, Daira Sanieh had been used as a collateral for one of the ruler's loans gone bad, and after 20 years of government management the company was still in the red. The subsequent privatization of Daira Sanieh courtesy of Cassel et compagnie not only removed 100 percent of the agricultural conglomerate to the private sector, but also involved the founding of a modern agro-industrial base, created a local landed gentry and sparked an unprecedented era of large capital investments and economic well-being. Much of this would not have been possible without the existence of a modern commercial bank of issue.

Up until its nationalization in the late 1950s, the National Bank of Egypt answered to a board of directors and its elected governor. From Sir Elwin Palmer in 1898 down to Sir Edward Cook in 1940, the bank's chief executive was always British which led critics to observe that not only was it a colonial bank, but its membership was closed to all but the cream of the English rank and file in Egypt. In a sense they were not far off. This was no rags to riches bank that grew because of ordinary depositors' savings. This was a trail blazing institution which, from its outset, was meant to serve British trade and colonial interests. Up until then, Egypt had depended in most part on French banks and financiers for its liquidity and commerce.

With the creation of the National Bank of Egypt, Britain could actively pursue its stringent policy of fiscal reforms aimed at enhancing investments in land, irrigation and transport, with the hope of setting off a splurge of capital accumulation.

Because the National Bank was a pivotal component of these socio-economic reforms, it was of paramount importance to legitimize its position as an 'Egyptian' bank. This did not happen overnight. At first the board's composite was mostly British with a Levantine mix and an ex-premier thrown in just in case.

Gradually, as the pashas increased in numbers, the British became less conspicuous. It was only when, on his own merit, former finance ministerAli Chamsi Pasha became the bank's first Egyptian president in 1940 that the "Egypt" in the bank's name started to mean something. Along with Chamsi came the titans of Cairo's Wall Street.

Chamsi was also the last pasha-president to head the bank before it was formally taken over by the state in February 1960.

The bank did not have to wait long to loose its prestige as the oldest and most important central bank in the Middle East. First to go was the sedate atmosphere when the bank's Pall Mall clubiness disappeared once the original rococo headquarter, built in 1900 by architect Dimitri Fabricius Bey, was replaced by what is today the Central Bank of Egypt, at the corner of Cherif and Kasr al-Nil Streets.

Then came the double whammy when the bank was nationalized and a new central bank created. The knockout blow came with the demise of the private sector following the promulgation of the socialist laws in July 1961. For the next three decades the National Bank of Egypt would be reduced to a mangy government clearing house.

Almost a century to the day from the sale of Daira Sanieh, Egypt is once more on the threshold of change.Somehow, we have come full circle just in time for the nation's oldest bank to celebrate its first centennial.