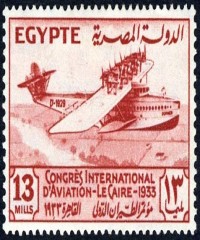

A flying boat is a fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water, that usually has no type of landing gear to allow operation on land . It differs from a floatplane as it uses a purpose-designed fuselage which can float, granting the aircraft buoyancy. Flying boats may be stabilized by under-wing floats or by wing-like projections (called sponsons) from the fuselage. Flying boats were some of the largest aircraft of the first half of the 20th century, exceeded in size only by bombers developed during World War II. Their advantage lay in using water instead of expensive land-based runways, making them the basis for international airlines in the interwar period. They were also commonly used for maritime patrol and air-sea rescue.

Their use gradually trailed off after World War II, partially because of the investments in airports during the war. In the 21st century, flying boats maintain a few niche uses, such as dropping water on forest fires, air transport around archipelagos, and access to undeveloped areas. Many modern seaplane variants, whether float or flying boat types, are convertible amphibious aircraft where either landing gear or flotation modes may be used to land and take off.

Early pioneers

The Frenchman Alphonse Pénaud filed the first patent for a flying machine with a boat hull and retractable landing gear in 1876, but Austrian Wilhelm Kress is credited with building the first seaplane Drachenflieger in 1898, although its two 30 hp Daimler engines were inadequate for take-off and it later sank when one of its two floats collapsed

On 6 June 1905 Gabriel Voisin took off and landed on the River Seine with a towed kite glider on floats. The first of his unpowered flights was 150 yards. He later built a powered floatplane in partnership with Louis Blériot, but the machine was unsuccessful.

Other pioneers also attempted to attach floats to aircraft in Britain, Australia, France and the USA.

On 28 March 1910 Frenchman Henri Fabre successfully flew the first successful powered seaplane, the Gnome Omega-powered hydravion, a trimaran floatplane. Fabre's first successful take off and landing by a powered seaplane inspired other aviators and he designed floats for several other flyers. The first hydro-aeroplane competition was held in Monaco in March 1912, featuring aircraft using floats from Fabre, Curtiss, Tellier and Farman. This led to the first scheduled seaplane passenger services at Aix-les-Bains, using a five-seat Sanchez-Besa from 1 August 1912 The French Navy ordered its first floatplane in 1912

In 1911-12 François Denhaut constructed the first seaplane with a fuselage forming a hull, using various designs to give hydrodynamic lift at take-off. Its first successful flight was on 13 April 1912. Throughout 1910 and 1911 American pioneering aviator Glenn Curtiss developed his floatplane into the successful Curtiss Model D land-plane, which used a larger central float and sponsons. Combining floats with wheels, he made the first amphibian flights in February 1911 and was awarded the first Collier Trophyfor US flight achievement. From 1912 his experiments with a hulled seaplane resulted in the 1913 Model E and Model F, which he called flying-boats

In February 1911 the United States Navy took delivery of the Curtiss Model E, and soon tested landings on and take-offs from ships using the Curtiss Model D

In Britain, Captain Edward Wakefield and Oscar Gnosspelius began to explore the feasibility of flight from water in 1908. They decided to make use of Windermere in the Lake District, England’s largest lake. The latter's first attempts to fly attracted large crowds, though the aircraft failed to take off and required a re-design of the floats incorporating features of Borwick’s successful speed-boat hulls. Meanwhile, Wakefield ordered a floatplane similar to the design of the 1910 Fabre Hydravion. By November 1911, both Gnosspelius and Wakefield had aircraft capable of flight from water and awaited suitable weather conditions. Gnosspelius's flight was short-lived as the aircraft crashed into the lake. Wakefield’s pilot however, taking advantage of a light northerly wind, successfully took off and flew at a height of 50 feet to Ferry Nab, where he made a wide turn and returned for a perfect landing on the lake’s surface.

In Switzerland, Emile Taddéoli equipped the Dufaux 4 biplane with swimmers and successfully took off in 1912. A seaplane was used during the Balkan Wars in 1913, when a Greek "Astra Hydravion" did a reconnaissance of the Turkish fleet and dropped 4 bombs

Birth of an industry

In 1913, the Daily Mail newspaper put up a £10,000 prize for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic which was soon "enhanced by a further sum" from the Women's Aerial League of Great Britain

American businessman Rodman Wanamaker became determined that the prize should go to an American aircraft and commissioned the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to design and build an aircraft capable of making the flight. Curtiss' development of the Flying Fish flying boat in 1913 brought him into contact with John Cyril Porte, a retired Royal Navy Lieutenant, aircraft designer and test pilot who was to become an influential British aviation pioneer. Recognising that many of the early accidents were attributable to a poor understanding of handling while in contact with the water, the pair's efforts went into developing practical hull designs to make the transatlantic crossing possible

At the same time the British boat building firm J. Samuel White of Cowes on the Isle of Wight set up a new aircraft division and produced a flying boat in the United Kingdom. This was displayed at the London Air Show at Olympia in 1913. In that same year, a collaboration between the S. E. Saunders boatyard of East Cowes and the Sopwith Aviation Company produced the "Bat Boat", an aircraft with a consuta laminated hull that could operate from land or on water, which today we call an amphibious aircraft The "Bat Boat" completed several landings on sea and on land and was duly awarded the Mortimer Singer Prize It was the first all-British aeroplane capable of making six return flights over five miles within five hours

In the U.S. Wanamaker's commission built on Glen Curtiss' previous development and experience with the Model F for the U.S. Navy which rapidly resulted in the America, designed under Porte's supervision following his study and rearrangement of the flight plan; the aircraft was a conventional biplane design with two-bay, unstaggered wings of unequal span with two pusher inline engines mounted side-by-side above the fuselage in the interplane gap. Wingtip pontoons were attached directly below the lower wings near their tips. The design (later developed into the Model H), resembled Curtiss' earlier flying boats, but was built considerably larger so it could carry enough fuel to cover 1,100 mi (1,800 km). The three crew members were accommodated in a fully enclosed cabin.

Trials of the America began 23 June 1914 with Porte also as Chief Test Pilot; testing soon revealed serious shortcomings in the design; it was under-powered, so the engines were replaced with more powerful engines mounted in a tractor configuration. There was also a tendency for the nose of the aircraft to try to submerge as engine power increased while taxiing on water. This phenomenon had not been encountered before, since Curtiss' earlier designs had not used such powerful engines nor large fuel/cargo loads and so were relatively more buoyant. In order to counteract this effect, Curtiss fitted fins to the sides of the bow to add hydrodynamic lift, but soon replaced these with sponsons, a type of underwater pontoon mounted in pairs on either side of a hull. These sponsons (or their engineering equivalents) and the flared, notched hull would remain a prominent feature of flying boat hull design in the decades to follow. With the problem resolved, preparations for the crossing resumed. While the craft was found to handle "heavily" on takeoff, and required rather longer take-off distances than expected, the full moon on 5 August 1914 was selected for the trans-Atlantic flight; Porte was to pilot the America with George Hallett as co-pilot and mechanic.